Scientists discover first known animal that doesn't breathe

This is the first animal on Earth proven to have no mitochondrial genome and no way to breathe.

When the parasitic blob known as Henneguya salminicola sinks its spores into the flesh of a tasty fish, it does not hold its breath. That's because H. salminicola is the only known animal on Earth that does not breathe.

If you spent your entire life infecting the dense muscle tissues of fish and underwater worms, like H. salminicola does, you probably wouldn't have much opportunity to turn oxygen into energy, either. However, all other multicellular animals on Earth whose DNA scientists have had a chance to sequence have some respiratory genes. According to a new study published today (Feb. 24) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, H. salminicola's genome does not.

A microscopic and genomic analysis of the creature revealed that, unlike all other known animals, H. salminicola has no mitochondrial genome — the small but crucial portion of DNA stored in an animal's mitochondria that includes genes responsible for respiration.

Related: These bizarre sea monsters once ruled the ocean

While that absence is a biological first, it's weirdly in character for the quirky parasite. Like many parasites from the myxozoa class — a group of simple, microscopic swimmers distantly related to jellyfish — H. salminicola may have once looked a lot more like its jelly ancestors but has gradually evolved to have just about none of its multicellular traits.

"They have lost their tissue, their nerve cells, their muscles, everything," study co-author Dorothée Huchon, an evolutionary biologist at Tel Aviv University in Israel, told Live Science. "And now we find they have lost their ability to breathe."

That genetic downsizing likely poses an advantage for parasites like H. salminicola, which thrive by reproducing as quickly and as often as possible, Huchon said. Myxozoans have some of the smallest genomes in the animal kingdom, making them highly effective. While H. salminicola is relatively benign, other parasites in the family have infected and wiped out entire fishery stocks, Huchon said, making them a threat to both fish and commercial fishers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

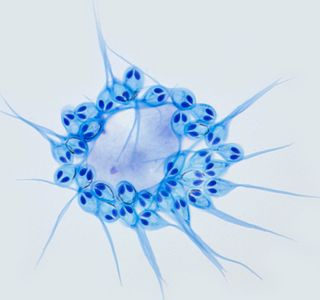

When seen popping out of the flesh of a fish in white, oozing bubbles, H. salminicola looks like a series of unicellular blobs. (Fish infected with H. salminicola are said to have "tapioca disease.") Only the parasite's spores show any complexity. When seen under a microscope, these spores look like bluish sperm cells with two tails and a pair of oval, alien-like eyes.

Those "eyes" are actually stinging cells, Huchon said, which contain no venom but help the parasite latch onto a host when needed. These stinging cells are some of the only features that H. salminicola has not ditched on its journey of evolutionary downsizing.

"Animals are always thought to be multicellular organisms with lots of genes that evolve to be more and more complex," Huchon said. "Here, we see an organism that goes completely the opposite way. They have evolved to be almost unicellular."

So, how does H. salminicola acquire energy if it does not breathe? The researchers aren't totally sure. According to Huchon, other similar parasites have proteins that can import ATP (basically, molecular energy) directly from their infected hosts. H. salminicola could be doing something similar, but further study of the oddball organism's genome — what's left of it, anyway — is required to find out.

- The 10 strangest animal discoveries of 2019

- Ick! 5 Alien parasites and their real-word counterparts

- The 10 most diabolical and disgusting parasites

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.

Most Popular